Nothing happens for ages and then lots of little things happen all at once. It’s a feast or a famine round here.

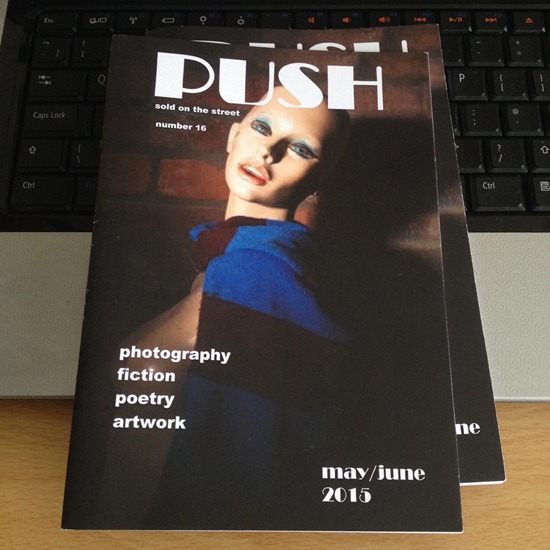

Later this week you’ll be able to buy the latest issue of PUSH, a magazine edited by Joe England which continues to go from strength to strength, selling out its ever increasing print runs in record time. My story, Amelia, is in issue 16.

I’ll also have a story called Notes From Some Other War appearing in Wyrd Daze. No publication date yet. You could probably call it a very loose and vague HPL mythos story. Or maybe you couldn’t. I don’t know.

I sold another story to the world’s premier science journal Nature. (Every time I sell a story to the “world’s premier science journal” I cackle at the sheer audacious absurdity of such an event ever transpiring) It’s my fifth story for those guys. God bless ‘em. It’s called Like Buses and will probably appear in a month or two.

What else, I’ve been navigating rivers in a vain and arrogant quest for enlightenment and a story. The river in question had to be walked in three stages, from sea to source, and I’ve currently written the account of the first leg only, which came in at 6000 words. Not sure what I will, or can, do with this. It’s going to be an awkward size – too long for some venues, not long enough for others. Perhaps some journal might serialise it. Who knows. It will appear though, even if I have to just bung it up on the web.

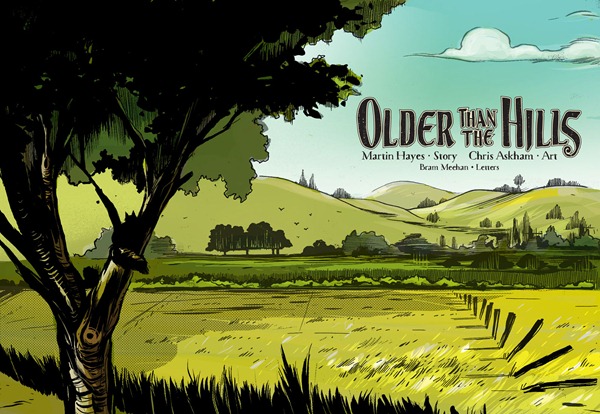

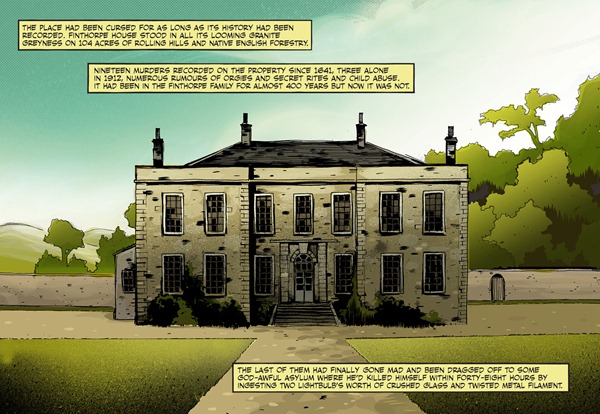

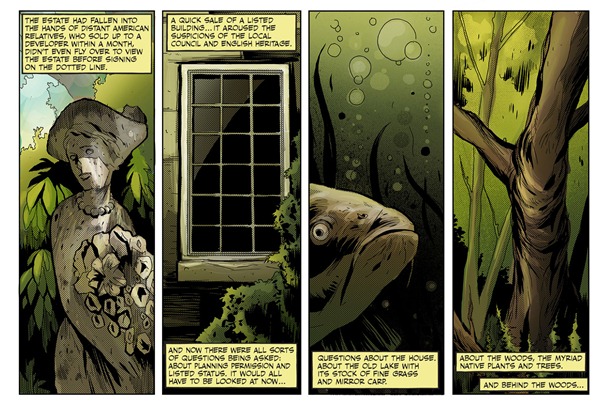

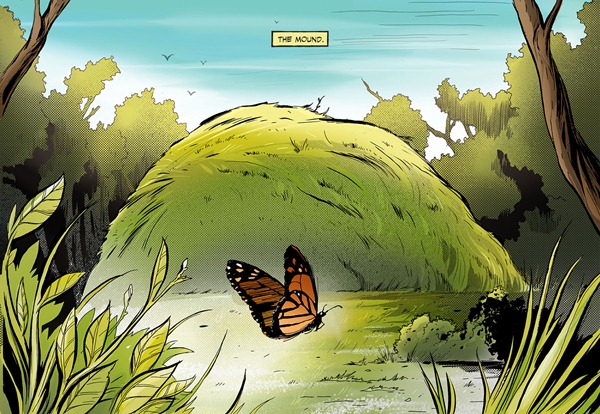

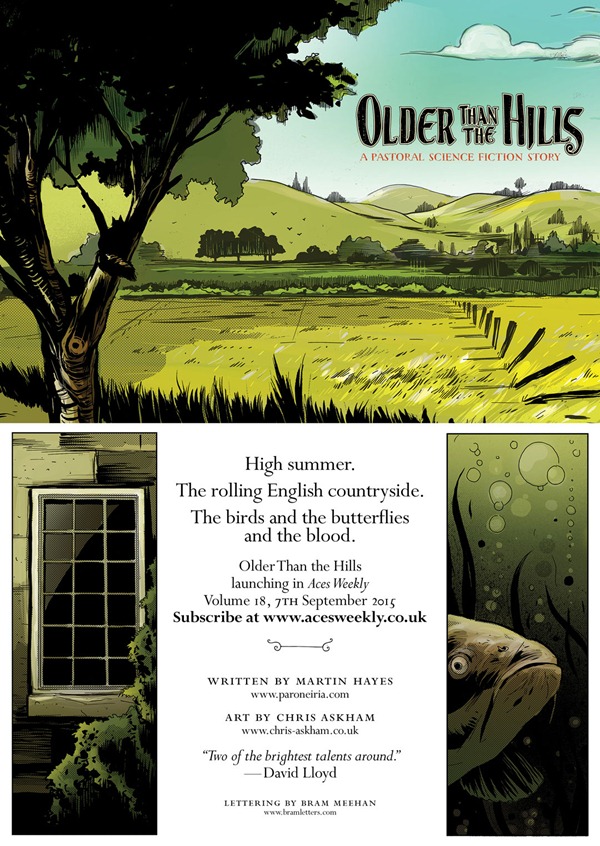

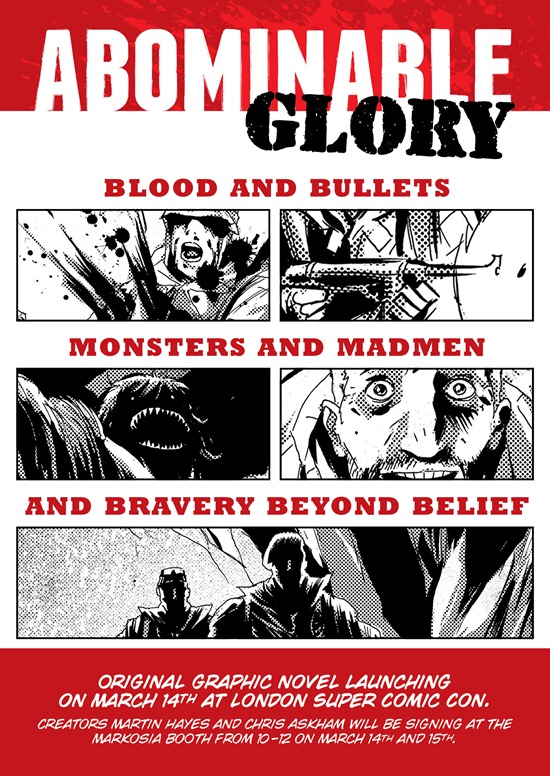

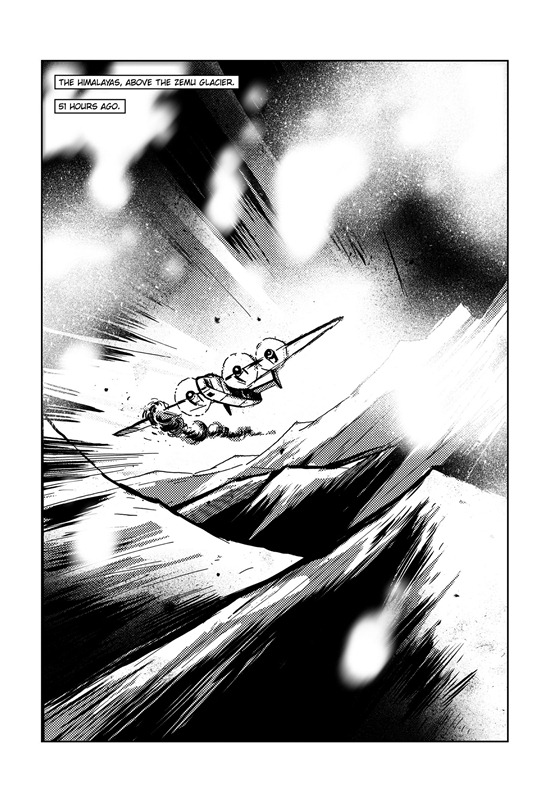

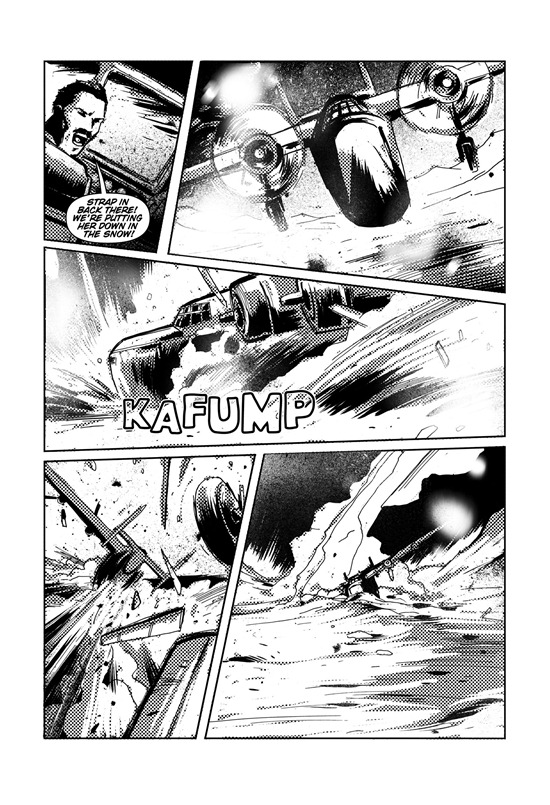

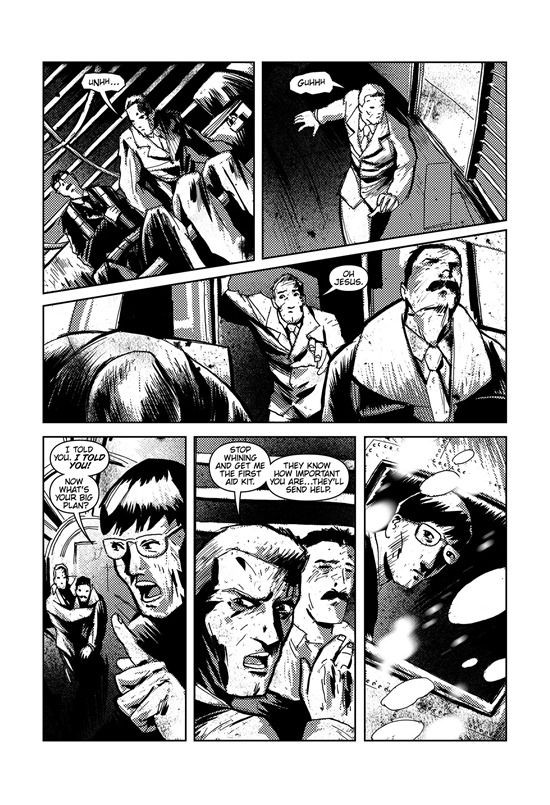

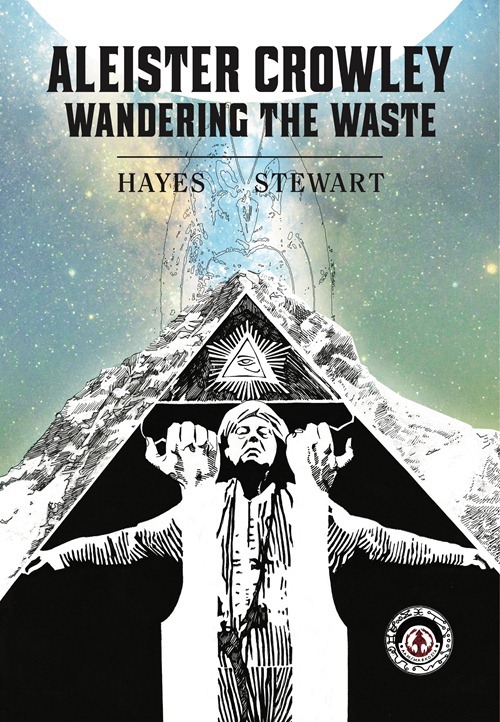

STOP PRESS! We’re getting the band back together. Fresh from the yeti-sized triumph that was Abominable Glory, the creative team of Martin Hayes (writer), Chris Askham (artist), and Bram Meehan (letterer/designer) are back at it with an all new comic project. Not out until September and all ultra hush-hush for now, but keep your eyes peeled because this is going to be good. A bit weird too, as it means I’m now getting emails from one of the real greats of the comic industry, whose work is one of the reasons I wanted to get into this lark in the first place. All will be revealed.

What else? I’ve been reading a lot about W.B. Yeats and his relationship with Aleister Crowley (oh fuck, not Crowley again) for a little article I’m writing. And George Russell, too, who went by the name AE. I’m beginning to see George Russell for what he really was: Ireland’s truest genius and visionary.

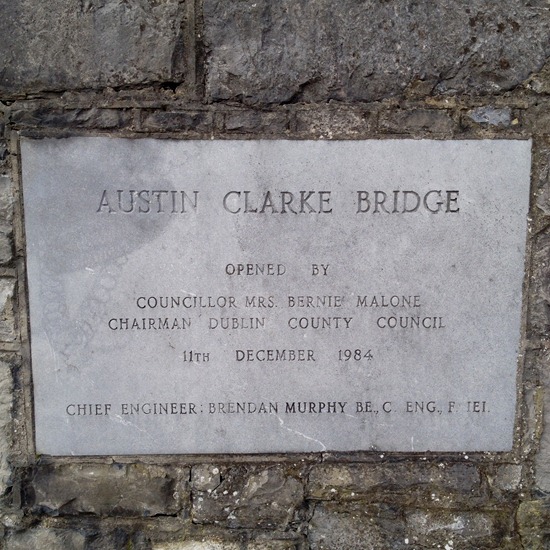

Work on another project had me reading both volumes of Austin Clarke’s autobiography and, indeed, a trip to the site upon which his house used to stand was called for, way out in Templeogue. The house is now demolished, wiped from the surface of the earth to widen a road and a bridge. Perhaps embarrassed at their own impudence, the authorities renamed the bridge in his honour, staged a grand ceremony and unveiling, but didn’t bother inviting any of his family members. Ireland, my Ireland.

Clarke had lived in England for many years with his wife and three children when, in 1937, he began to grow uneasy, fearful in his bones that another war was in the offing. He wired funds to his mother in Ireland with instructions to buy a house for him to return to. Several were looked at before Clarke decided on Bridge House in Templeogue.

Clarke’s mother, a god-fearing woman, had always been dismayed at her son’s lack of faith, at the fact that all his fiction had been banned in Ireland by the Censorship of Publications Board, and so, she took her son’s money and bought the house at Templeogue as he’d requested. But it was only when Clarke arrived back in Ireland, ready to move in, that he learned his mother had bought the house with his money but in her name, and arranged through an arcane legal mechanism known as usufruct that he would have only a life interest in it. Upon Clarke’s (and his wife’s) death, the house would pass, free of charge, lock, stock and barrel, into the hands of the Catholic Church. To the Propagation of the Faith, to be exact.

What a nice pious lady she must have been. To do that to her son.

Clarke’s poem, Usufruct, written at Bridge House, begins…

This house cannot be handed down.

Before the scriven ink is brown,

Clergy will sell the lease of it.

Do yourself a favour, go and read some of Austin Clarke’s work. It’s all well worth a look. Here, this’ll get you started.